Formula 1 wouldn’t be Formula 1 if it wasn’t spiced up with some controversy from time to time, and on multiple occasions in the previous years the controversy stemmed from the so-called “flexi wings”, i.e. flexible wings.

During the epic 2021 season there was a kerfuffle surrounding the wings of both Red Bull Racing and Mercedes, and earlier this year Helmut Marko pointed the finger of blame on McLaren and Mercedes, who both supposedly had an illegal front wing.

And during last weekend’s Azerbaijan Grand Prix it was McLaren who was accused again, as it seems that the DRS slot opens by itself under larger loads.

The engineering

Before we start to make McLaren out as cheaters, let us first have a look at the engineering behind the wings and DRS.

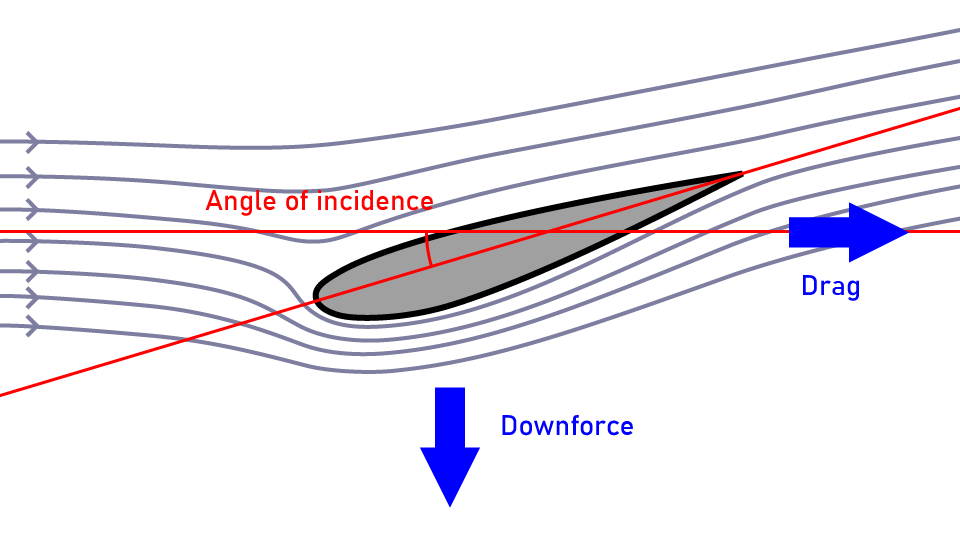

A wing on an Formula 1 car works just as the wing on an airplane, only upside down. Where an airplane procudes lift, a Formula 1 wing produces downforce, and in both cases drag is produced.

An aerodynamic load, as displayed in the image below, also produces a deformation of the aerodynamic element, which in turn changes the aerodynamic load, which in turn procudes a deformation et cetera. This synergy is called aeroelasticity and is the result of the impossibility to make constructions infinitely rigid.

Teams try to exploit this effect by letting the wing bend at higher speeds, so that it produces less drag, and thus a higher top speed is obtained. In the turns the wing rights itself up to the normal position, and the necessary downforce to make the corners is restored.

The Drag Reduction System (DRS) was introduced in 2011 to, as the name implies, reduce the drag of the car. It does so by decreasing the incidence of the top element of the rear wing. This action is performed using a standard component which can be activated by the driver at certain moments and certain positions on track.

The rules

When at the end of the 1990’s multiple heavy accidents happened with rear wings separating from the cars the FIA decided to clamp down on this and enforce a minimal rigidity for the wings. However, theoretical rules and real life don’t always align.

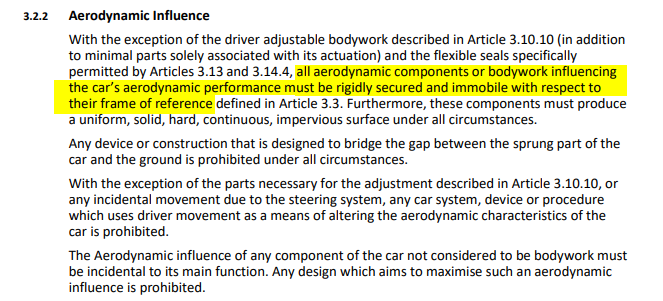

According to rule 3.2.2. of the 2024 Technical Regulations (version 31 July 2024) all aerodynamic parts must be rigid, but in practice this is impossible, because constructions cannot be made infinitely rigid as stated before. This means that a certain amount of flexibility has to be tolerated. The FIA has defined a number of static tests which the wings and other aerodynamic components have to pass. Only then is the car deemed legal. All tests are described in rule 3.15 of the 2024 Technical Regulations (version 31 July 2024).

The FIA notes that it can use the on-board cameras to monitor the flexibility of the rear wings, meaning that if they feel something is off they can issue a Technical Directive to mitigate the issue. This has been done in the previously mentioned cases in 2021.

The biggest issue with these tests however is the fact that they are only point loads or very local loads, whereas the downforce and drag are a distributed load over the entire wing span. This means the tests can only simulate a specific resultant force rather than the actual load with all its aeroelastic intricacies.

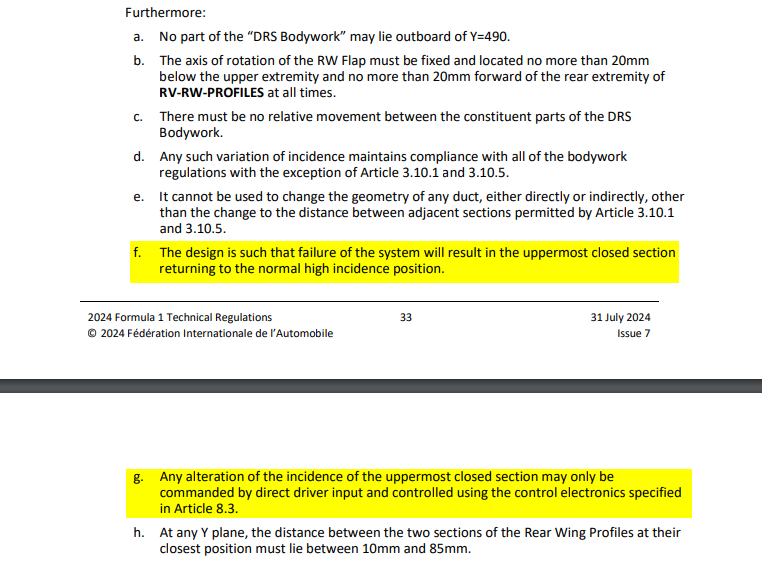

DRS has additional rules applied (thanks to @umakshually on Twitter for looking these up). There is the fact that the upper, movable element should return to its normal position in case the system fails, and the fact that the incidence can only be altered by direct driver input. For more details see rule 3.10.10 of the 2024 Technical Regulations (versie 31 juli 2024).

The case

So what is the actual issue with the McLaren MCL38? Observant viewers noticed that the DRS of McLaren opened up ever so slightly at high speeds, but closed again on lower speeds. This can be seen quite clearly in the tweet by @f1multiviewer below.

https://www.twitter.com/f1multiviewer/status/1835331158675951966

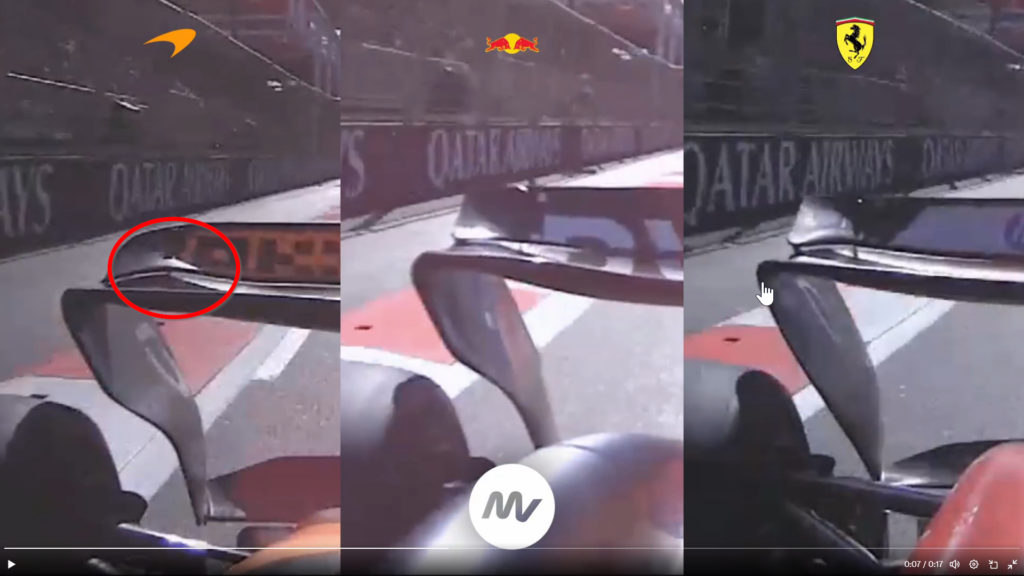

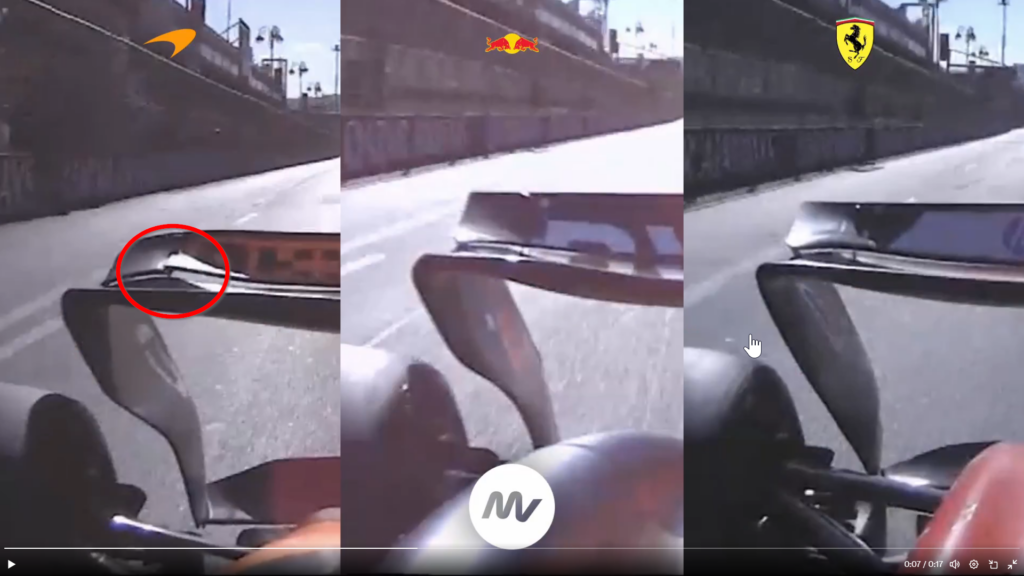

It is clear that all three wings (respectively those of McLaren, Red Bull Racing and Ferrari) in the video bend back in upright position as the load decreases, but McLaren’s wing also shows a small gap closing near the hinge point of the upper wing element. The video clearly shows that it occurs only there, not further towards the center of the wing. For clarity the difference is marked in the images below.

Although the gap is small, it could prove to be a small advantage, which can be quite significant in this year’s battle for the championship.

The verdict

The main question is of course: is this legal? By definition any moving aerodynamic parts are illegal, but in practice a car is only deemed illegal if it fails the flexibility tests, excluding the DRS element.

So the rules regarding the flexibility do not provide a clear conclusion, so one needs to look at the rules regarding DRS. Items f. and g. from the list mentioned above are picked for a reason, as they mention the neutral and activated position of the upper element.

Items f. talks about the fact that the upper element must return to its normal, higher incidence position if the system fails, e.g. there is an issue with the actuator or the software. This is hardly applicable in this case, as there is no mention of a DRS failing, but it could be considered a potential safety issue.

Item g. is interesting however, and could yield a possibility to sanction McLaren, as the incidence is changed without the intervention of the driver or the control electronics. There are however two objections to this argument.

Firstly, the rule states the “alteration of the incidence of the uppermost closed section”, which implies that the element as a whole is rotated. In McLaren’s case however, it seems that there is only a local alteration of the incidence as a result of the wing twisting. Which McLaren can easily use as an argument that it is not an alteration of the incidence of the entire element.

Secondly, the rule state that the alteration “may only be commanded by direct driver input”. This means that the FIA has to prove that the gap in the rear wing is indeed “commanded” by the aerodynamic load (i.e. an intentional result of the wing design) rather than a side-effect.

All things considered there is little that points to McLaren doing something actually illegal, but this is certainly something unforseen in the regulations. The actual advantage they have remains to be seen, but it surely will spark an interesting discussion.

As audience we can be quite sure that the FIA will close this loophole sooner than later using a TD, since McLaren is clearly operating in a grey area. But until that moment it looks like McLaren has done their homework, and that is reflected by their lead in the constructors’ championship.